The kill zone from small arms ground fire is between 50 and 1,500-feet altitude above ground level. Good tactics was to avoid flying in this kill zone for obvious reasons.

The kill zone from small arms ground fire is between 50 and 1,500-feet altitude above ground level. Good tactics was to avoid flying in this kill zone for obvious reasons.

Tactical combat flying is vastly different from the basics of flight school training. Flight school teaches basic helicopter systems including operating limitations for rotor systems, mechanical controls, hydraulic, engine, main transmission system temperature and pressure limits. Actual flying skills are very basic and rudimentary – learn to walk before you can run.

Flight maneuvers are taught using a standardized methodology – take-offs, landings, airspeeds, power requirements, emergency procedures. All learned in a basic format to prepare a future pilot with the knowledge and skill to develop his performance level as well as that of the aircraft.

Once in tactical combat flying, those basic skills must become second nature – now there was no instructor pilot to correct your mistakes and save your ass. Combat flying demands that aircraft control is a reactionary part and an extension of you.

After a few weeks of in-country orientation and familiarization, operational flying started. Before regular duty assignments there is the ‘local area orientation’ – getting to know the company area, the flight line, operations procedures, aircraft maintenance, etc. Every second or third day would be flying in the airfield traffic pattern resurrecting and improving on flight school lessons.

Once you received initial approval from two or three different veteran pilots, you would go into regular crew rotation flying ‘slicks.’ But only as a co-pilot – much more was required before you were approved to be an aircraft commander.

The a/c taught the safest approach and departure routes at field locations, interpreting terrain features against map coordinates. Utilizing high overhead approaches into field locations to minimize exposure to enemy ground fire. Determining the best and safest operational profile for both aircraft and crew.

Slicks were the troop carriers, cargo haulers, administration missions, and personal observation chariots of the various battle commanders. So named because they carried no external side armament or weapons systems. Two M-60 7.62 mm machine guns manned on either side by door gunners riding in open doorways. Total crew compliment of four. FNGs were always assigned to senior flying crews – guys with experience in both flight and operational knowledge of and in the area of operations.

There were basically two daily missions for the slicks. Two helicopters were assigned to each of the battalions in the 196th Light Infantry Brigade (LIB). One was designated as the command & control (C&C) aircraft for the battalion staff, the other would be used as a general transport hauling personnel, ammo, water, etc. from the battalion rear areas to the field units. The battalion operations center could mix, and match missions and uses at their discretion.

When not engaged in daily support missions, the slicks would be employed for combat assaults. Large helicopter formations carrying platoon or company size units into battle areas. The lightly armed slicks were sometimes easy prey from enemy ground fire. Elements of the 71st armed platoon commonly provided reconnaissance by fire and live covering fire support to the troop-carrying slicks during combat assault operations.

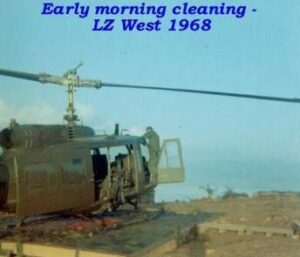

Unfortunately for the 71st, its area of operation was located some 30 miles north of the Chu Lai home base. Other 14th CAB units staged from their home bases – the 71st had a 30-minute daily commute to their assigned mission. Early morning departures at o-dark-thirty to LZs Baldy, Center, East, Ross, West.

Truthfully these particular locations were really artillery fire support bases with a co-located battalion headquarters operations center (BTOC). Usually, a small landing pad for the C&C bird and the resupply bird.

Although arriving early, the ‘hurry up and wait’ game was always played. Sitting on the C&C pad for hours waiting for the battalion commander to leave the BTOC for his daily visitation and tour of his field units. Re-supply birds were kept busy throughout the day shuttling back and forth with ammo, food, pax, or other miscellaneous materials.

Another important favor for the grunts was mail pick up. Often while waiting for re-supply off-loading or maybe the Colonel is busy chit-chatting, a lone soldier would approach the helicopter carrying a handful of letters to be carried back to Chu Lai and deposited in the mail system. Lots of trust to ensure those letters got mailed home.

Flying C&C could be fun depending on the colonel’s mission and mood. Usually accompanied by the battalion sergeant major (probably the colonel’s bodyguard), maybe the operations officer, the radio telephone operator (RTO), and a few other staffers privileged to get off the wretched LZ for a few hours and log some flight time entries for an Air Medal adding to their ribbon rack. Most C&C flights devolved into Chaos & Confusion – half the time the colonel didn’t know where he was and had to rely on 20-year-old helicopter pilots to get him to his destination.

The ultimate Chaos and Confusion occurred during large combat assault operations. Flight lead would be inbound, gunships would be scouting ahead, Smokey (smoke ship) would lay down an obscuring smoke cloud to obstruct enemy ground vision – all would be proceeding smoothly until the Colonels would break into the radio networks with last minute instructions, advice, stupid questions, etc.

The Chaos and Confusion aircraft high above would be the higher-up Colonel (HUP) who would contemplate, interpolate, obfuscate, and pontificate the ongoing operation. Resulting in more confusion. Always a disaster.

The first flight of the day would depart late morning after hours of waiting around, sleeping in the helicopter, choking down cold C-rations, and just hanging out.

Since this was the military version of a VIP mission, the crew chief and door gunner doubled as footmen and doormen for the battalion riders. Assisting them on and off the aircraft, managing the seating arrangements, and controlling any other cargo in the cabin area.

No seat belts required, and tray tables always remained up & locked – if only there were tray tables. Business class seating was next to the large open cabin doors – better views and cooler breezes. Economy class sat on the floor – the adventurous could dangle their feet outside the helicopter into the 100 mph air-stream.

Only after clear left & clear right was announced by the crew chief and door gunner would the helicopter depart for the grand tour. The typical route of flight would be flying back and forth between each unit field location. The colonel and staff would disembark to check on troop status, confer with the appropriate unit commander, deliver words of wisdom, or get an update on vital intelligence.

The crews stayed in the helicopter in case a quick departure was required. Often before takeoff there were those heroic live fire displays by the colonel and sergeant major – both advancing rearward to the helicopter tossing grenades and firing their M-16s on full auto thus insuring our safe departure. Bronze Star stuff and a daily bulletin write up for sure.

Flying on oversight terrain surveys, the colonel would often request to fly lower. Sitting in the open cabin doorway, looking through his field glasses he would remark, ‘fly lower, can you fly lower so I can see better!’ The colonel didn’t understand the kill zone but to avoid the kill zone and in order to accommodate the request, we would perform a series of slow lazy sky turns while ‘dialing down’ both aircraft altimeter indicators.

Rolling out over the survey area and pointing to the now lower altitude dial reading the colonel would remark, ‘yeah, yeah, I can see much better.’ Never underestimate warrant officer pilots. And always stay out of the kill zone.

(c) Copyright – 2023 Vic Bandini