Age of Aquarius – August 1969

“I missed the Age of Aquarius, but I saw it on TV.”

Nelson Demille – Word of Honor

R&R in Sydney, Australia the last week of July was a welcome break after nine months in Vietnam. Leaving the summer heat and humidity for the mild winter in the Southern Hemisphere proved to be very relaxing. Real food, the comfort of a hotel bed, ‘inside’ plumbing with lots of soap and hot water. Zager and Evans sang In the Year 2525. Neil Armstrong had landed on the moon a several days earlier. At that moment Neil and I shared the same goal – return home quickly and unharmed.

The last flight mission before R&R was a Dust-Off medical evacuation escort over the Hoi-An river. The Dust-Off helicopter had to land on the narrow bridge roadway that crossed over the river.

The Hoi-An area was usually ‘hot’ and sitting atop the bridge could prove to be an inviting target. Circling above the bridge as the wounded were quickly loaded on the Dust-Off, the Firebirds provided covering fire and an ominous presence to would be enemy shooters. Luckily the mission experienced no ground fire, and all returned safely and then me on my way the next day to Sydney for seven days R&R.

Back to the war – Victor Charlie wasted no time with me back in the AO. No time in fact as my first day back from Sydney found me on standby at Baldy. Early August, Sunday evening at LZ Baldy – beautiful weather watching blue skies and puffy white clouds from outside the Firebird’s standby hooch. The brigade TOC hotline rang in the Firebirds standby hootch the– a U.S. platoon was pinned down by a sniper in a church bell tower. The church was in the middle of a small hamlet several miles southwest of Baldy along the road to Que Son and LZ Ross.

Once on station the ground commander advised his platoon’s location before commencing the attack on the bell tower. After circling overhead, I fired a pair of rockets with one striking directly inside the bell tower louvres opening and into the sniper’s shooting perch (rocket was a GGR – God guided rocket!). The exploding rocket blew out the opening forever silencing the sniper and simultaneously ringing the church bell. Pass the collection plate for needed repairs.

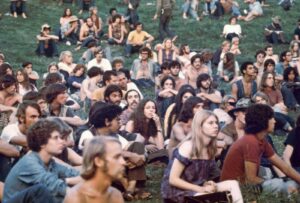

Welcome to August 1969. It was the Age of Aquarius. While the hippies were drinking and doping out in the rain and soggy muck at the Woodstock celebration, the 196th brigade grunts were mired in the heat and gore of combat.

When Woodstock began on August 15, Kelly McHugh – Firebird 97 would be wounded the next day after completing a routine fire support mission (there were no routine fire support missions).

After transferring aircraft controls to his co-pilot Robert Combs a ChiCom .51 cal. round passed through the right side of the helicopter and severed Kelly’s left leg below the knee, blew off the pilot’s collective control head, then deflected 90* toward the rear of the helicopter lodging in the main transmission housing.

That is a lot of energy.

Combs pressed inbound to LZ Baldy for the medical aid station where he landed the heavy gunship inside 60’ x 60’ landing area surrounded by high commo wires. While enroute to Baldy John Wiklanski and Jim Hiler lowered Kelly’s pilot seat rearward and Ski, using his web belt, applied a tourniquet to Kelly’s blood spurting leg, no doubt saving his life. We monitored Combs progress toward Baldy and met him when he landed.

When Kelly was lifted from the pilot’s seat his left leg hung by a sliver of flesh to his knee. The crippled gunship had to be moved quickly off the aid station pad to allow any other inbound wounded. I jumped into the co-pilot’s seat and prayed to get a start not knowing the extent of damage to the throttle or collective control mechanisms. Fortunately got it started and moved off to the Baldy Firebirds main landing area. A heavy lift Chinook helicopter would slingload the damaged gunship back to Chu Lai a few days later.

My replacement crew would spend the Woodstock celebration days flying and fighting for the living and dying soldiers in the 3/21st and 4/31st Infantry Regiments. With Kelly out of action and now down to only two Fire Team Leaders (me 99’and KAZ ’92’) I remained on Baldy standby for the next five days until Captain Stan (’96) could be infused into rotation.

August 18, 1969, mission assigned to escort a badly needed resupply mission to several units of the 4th/31st that had been in deadly contact for days. The dead (KIAs) were stacked against the perimeter. Hostile ground fire prevented previous resupply of ammo, water, and food. Supplies were running low. Resupply was badly needed and the wounded evacuated. This mission had to be completed.

My Fire Team would provide cover and draw fire away from the resupply aircraft piloted by 1LT Shulsen. Ted was to fly treetop level into the LZ. The bad guys in the trees at his twelve o’clock position opened up when he landed. Torrents of automatic weapons fire tore through the front of the helicopter shattering the instrument panel and wounding Ted and his co-pilot. Shulsen screamed over the radio, ‘I’m hit, I’m hit!’ I could hear the ground fire through his open mic radio transmission.

As I flew in to cover Ted, the bad guys turned their attention on me. One of the bad guys fired an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) directly at me on the nose of the helicopter gunship, missing me only due to the ballistic ‘drop’ of the grenade projectile – that guy had me dead on, and dead. But we were lucky that day – he missed. The amount of ground fire, noise, radio chatter, etc. was unbelievable. Over 50 years later I can still see the RPG smoke wisp passing between the skids underneath my helicopter chin bubble.

I yelled over the radio to get the ship out of the LZ. But with both pilots wounded, the aircraft just sat running in the Landing Zone. No radio communication came from either Shulsen or Hart. I figured these guys were either dead or badly wounded because the ship just sat there running.

I briefed my crew and wingman that I would land in the LZ and my co-pilot would try to fly out the crippled ship. Just as we lined up for the descent and landing approach, Shulsen’s aircraft began wallowing off the ground, gaining altitude, and barely clearing the trees the bad guys are firing from. Shulsen called and said both he and his peter pilot were shot but he was able to fly the aircraft.

Shulsen flew the aircraft while holding his hand over the blood spurting head wound. His copilot Hart had been hit three or four times in his ‘chicken plate’ (bulletproof body armor) and had been knocked unconscious by the blows from the bullets striking his ‘chicken plate.’ Hart had also been hit in the leg, but he was alive – on his first and last flight.

Shulsen flew the aircraft to the closest friendly area at LZ Center crash landing onto its eastern ridge. Darkness was beginning to settle over the LZ as Shulsen and Hart were carried from the still running aircraft. No one on the ground able to shut the damn thing down. Sliding my gunship onto the east ridges alongside the still running slick, my co-pilot jumped into the waiting slick, then took off into the impending darkness for LZ Baldy with my gun team flying his escort. The slick had been so badly shot up that the electrical system was gone, the instrument panel was nothing more than a mass of shattered glass, and the hydraulics were beginning to fail. No instruments, no lights, no nothing as we pressed on into the darkness toward Baldy.

Bob landed the shot-up slick on the airfield at LZ Baldy. After the aircraft was finally shutdown the extent of the damage was telling. One main rotor blade had sustained a .51 caliber hit (12.7 mm – it was BIG anyway!) that entered on the bottom of the blade leading edge, penetrated completely through the chordwise blade span, and exited the top of the trailing edge. The main rotor blade had been cut almost in half. Other holes throughout the aircraft too numerous to count rendered it completely non-flyable. The slick was ‘hooked’ out the next day by a CH-47 ‘Chinook’ helicopter.

A humorous side story here is that Bob had landed the wounded slick very near the Firebird’s brand new ‘two holer’ latrine (it really was a nice, new outhouse!). When the ‘Hook’ hovered over the wounded slick for hook up/pick up, the tremendous down blast of the tandem rotors literally exploded the ‘two holer’ into a swirling storm of plywood, 2 x 4s, screen mesh, and corrugated metal pieces. What a shame!

The truly tragic ending to this story is that after surviving the horrific ground attack on their helicopter, Shulsen’s crew chief Stephen Martino and door gunner James Lavigne were killed the next day as they crewed a Rattler slick commanded by WO1 Gerry Silverstein. The aircraft, flying command & control, was caught in a crossfire, exploded and rolled in flight, and crashed in a fiery ball instantly killing the four-man crew and six staff personnel of the 3/21st Infantry Regiment Battalion staff.

Circling high above in his C&C helicopter the 196th brigade commander observed the entire event. Thankfully the Rattler pilot chose not to descend into the danger zone. The non-pilot unrated brigade commander returned to his headquarters at LZ Baldy and would later receive the Distinguished Flying Cross for his intense observation of the fire & brimstone that day.

The news of Silverstein’s shootdown was relayed to the Firebirds standby hooch by the 196th TOC. News of the fighting had caught the attention of the press. Oliver Noonan, a correspondent for UPI, who somehow managed to get aboard Silverstein’s helicopter perished when it was shot down. While waiting for more information at the Firebirds standby hooch, a ‘correspondent’ approached me asking for a ride to the shoot down area. Noonan was a fellow colleague and the correspondent later identified as Horst Faas was pushing me to get him out there. I refused him several times stating that it would be suicide for anyone to be in that area until more information was available. He eventually found his way into the area but on the ground and was present six days later August 25 when the bodies of the 3/21 shoot down were recovered.

Over the next few days, the unit supply officer would emerge from hiding in his darkened office and fly a resupply mission to this same unit – still in enemy contact, still in need of critical supplies, still taking casualties. The mission was successful and the normally not flying supply officer would be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross 45 years later. Better late than never and thanks to being close to the orderly room Army. Stars and Stripes Southeast Asia edition published photos and coverage of the Woodstock event.

Intense enemy activity would continue in this area for the remainder of the Summer ’69. The flying was relentless – every mission was dangerously hot. Firebirds gunships were critical in fire support missions to the 196th Light Infantry Brigade ground battalions. My last ‘hit’ was September 4 – a .51 cal. round striking the tail boom. Near Hill 352 in the same area as Silverstein and Kelly’s shooting.

The last two weeks of August 1969 would cost 116 American KIAs and almost 500 WIAs from both Army and Marine combat soldiers in this area known as Death Valley. This was the price paid for the Hiep Duc Resettlement Center, the glittering gem of Saigon’s model pacification program. The American soldiers successfully prevented the destruction of the Resettlement Center in what AMERICAL Division commanding general Lloyd Ramsay proclaimed it a ‘successful pre-emptive battle’.

Somebody in the White House was paying attention. In 1969, President Nixon issued a directive that all American units would immediately cease offensive actions. U.S. Forces were placed into defensive roles to reduce the continued loss of American military personnel. The final U.S. military operations ended in September 1971.

The Freedom Bird was five weeks away.

(c) Copyright – 2023 Vic Bandini