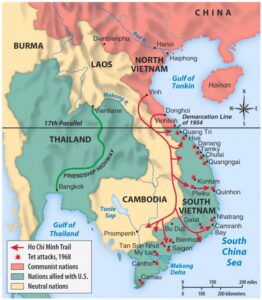

Tam Ky is the headquarters of Quang Nam Province in the then Republic of South Vietnam. Positioned along the QL1 (Highway 1) forty miles southeast of Danang and twenty miles northwest of Chu Lai, it sits along the Thien Phuc river, a mainline artery of the Ho Chi Minh trail.

The geographic location and topography were very strategic to the NVA and VC for the resupply of men and equipment streaming from North Vietnam along the mountain spine HCM trail between Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Because of its tactical military and logistical value, Tam Ky and the adjacent river valley were the sites of battles that cost the lives of many U.S. and enemy soldiers. It was a natural ‘flow through’ area to supply men and materiel both north to Danang and south toward Chu Lai.

The May 13, 1969, battle began near Nui Yon Hill a few miles away from the Tam Ky hamlet. The initial combat assault launched at 1030 hours with elements of Charlie Company, 3rd/21st Infantry Regiment. The 71st Assault Helicopter Company Rattlers provided the infantry ‘lift’ with the Firebirds aerial gunship fire support.

Once the artillery prep on the LZ stopped, Firebird gunships began providing covering fire for the inbound slicks. The ‘Birds strafed the LZ firing rockets and mini-guns with Firebird’s door gunners M-60s blazing away along the LZ perimeter to discourage any bad guys who might be lurking there. Charlie waited patiently.

The first lift elements were inserted without incident into a large football size field bordered by thick tree lines. The first element grunts hit the dirt quickly after jumping from the helicopters. As the second lift element was nearing touch down, massive automatic weapons fire erupted from the tree lines.

The grunts were immediately pinned down on the LZ. Before the second lift helicopters could clear the LZ on take-off, two helicopters were shot down, crashing upright onto the field. The third lift element, unable to land, performed a go around and returned to the original pick-up zone (PZ). The two downed slicks were now unprotected ‘sitting ducks.’

After several rescue attempts, the slick crews were successfully evacuated off the LZ. Following the reported rescue to Rattler operations, but unable to recover the downed aircraft due to the continued mass of enemy firepower, I received a radio call asking if I could ‘blow up’ the downed helicopters. ‘Roger that, I can do it’ acknowledged my call back to Operations.

I began my run on the targets, lined up, targets in my rocket sight, thumb on the rocket release button – – – – – ‘don’t shoot, don’t shoot,’ came the radio call from Rattler operations. I broke away from the target zone and called operations for confirmation. Someone in the rear made the decision not to destroy the downed aircraft. Why? Above my pay grade – so my gunship team returned to fire support the grunts on the ground.

We endured the the afternoon providing aerial fire support to both the Charlie Tigers and the Dust-Off helicopters flying out their wounded.

Never shutting down we continued to refuel and rearm at LZ Baldy logging over 7.4 flight hours until darkness set in. The grunts on the ground would remain in close combat and suffer thirteen killed and thirty wounded over the next three days of fighting.

Returning to LZ Baldy that evening an inspection of my gunship determined it unflyable. A replacement gun team arrived later that night and we returned to Chu Lai. The lame gunship was ‘Hooked out’ (air-lifted) the next day to aircraft maintenance.

Overnight the bad guys infiltrated the LZ and stripped both helicopters bare leaving only the airframes intact. Never understood the reason why I was stopped from destroying the downed aircraft. I was ready to fire – and in retrospect, should have. Could have claimed the radio transmission garbled and unable to understand. Should have just gone ahead and taken my chances – one will never know.

This was the absolute futility of the war with its confusing tactics that made no sense. U.S. forces had the firepower but lacked significant defeat of the enemy, no property acquisition or retention. We fight and we leave – only to return to the same areas in future engagements and with the same results, which were always, no results.

After the May 13 engagement I realized that this ‘war’ was never going to be won. Never. The stupidity of senior commanders with their tactical decisions was truly appalling – time to stay alive, hopefully unwounded, and return home.

During this same action we learned that Captain Paul Lukins was killed flying emergency re-supply into a hot field near LZ Professional. Paul was from Riverside, CA, and one of the best officers in the 71st – well-liked and respected by everyone. Paul was the first loss in 1969 and the first since October 1968.

The three-day fight shocked the once dormant 196th Area of Operations (AO). The combined losses of men and equipment overwhelmed the Brigade’s reserve forces. Several days later elements of the 101st Airborne Division were relocated to reinforce the 196th ground combat battalions and the 71st helicopter unit.

The bloody 1969 Summer Offensive began on May 13 with the Battle at Tam Ky. But Saigon savants however claimed this campaign did not begin until sometime in June. Coffee pot commandos needed time to evaluate the actual battle reports. Coordination with ‘higher headquarters,’ the UPI correspondents, and the South Vietnamese government goons had to all agree to the new phase of the war.

Unfortunately, and because of more urgent responsibilities, the field commanders who transmitted the gruesome battle accounts were unable to commiserate with the happy hour Hotel Caravelle cocktail connoisseurs.

(c) Copyright – 2023 Vic Bandini