……. because the Wall, for all its abstractness and metaphorical nuances, was in reality just a massive tombstone, a common grave with everyone’s name on it. Nelson Demille – Up Country

Most Memorials are remembrances for wartime service that are directed to the Fallen Warriors killed or wounded while involved in armed conflict or hostile events. Typical of active war fighter units, a Memorial service was held for those service members recently killed in battle. Soldier symbols, i.e., helmets, boots, rifles, etc. were often displayed while unit commanders memorialized the passing of the deceased combatants. Chaplains prayerfully reminded the living of their obligations to their fallen comrades to ensure passage to Valhalla.

There are others, while not directly involved in hostile activities, are nonetheless deserving of special recognition. Modern audio and visual communications have literally brought armed hostilities into the lives of everyday families and others. Many media reports are ‘real time’, unlike previous decades of written information that could take weeks to be received.

One of the most memorable media during the Vietnam years was CBS correspondent Walter Cronkite. The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite (and other notable newsers like the Huntley-Brinkley report) brought the TV war into living rooms during the evening dinner hour. Families watched with wonder while Uncle Walter heroically and stoically described the latest military operations in War Zone C along with the accompanying body counts, both American and enemy.

Families watched in ‘living’ color the dying soldiers and the massive destruction wrought by the daily fighting activities. Only in America.

Almost all reporting was focused on War Zones C & D and the fearsome sounding Iron Triangle – all in & around the Saigon area. The feeder correspondents and on-the-ground war reporters didn’t venture too far from homebase for fear of encountering the real war.

And with darkness comes Happy Hour at the Hotel Caravelle with their Pearl of the Orient paramours then followed by discriminating dining and luxurious living in the Cholon District. The mighty media moguls are eternally memorialized for keeping America updated on the war.

Families and others ‘at home’ endured the burden of The Nightly News. Wondering if someone they knew or worse that a family member had been wounded or possibly killed in the reported actions. Wishing and hoping for the news that was not the news everybody dreaded to learn. Not knowing was worse than knowing.

The information flow was slow at best – written letters took days; telephone communications were limited for ‘official business only’ and available to those fortunate few in the offices of major military commands or the large media channels covering the war. The anxious anxiety for those waiting was constantly consuming. It was the existence of day-to-day fears living and waiting in the unknown.

Ain’t no use in lookin’ down, ain’t no discharge on the ground. Ain’t no use in looking back, Jody’s got your Cadillac! Yes, the infamous and mythical Jody– that memorable character back home who not only had your Cadillac but who stole your girl after you left for service with Uncle Sam. Jody – the guy who kept your girl company while you enjoyed those lonely nights in the barracks with 40 others suffering the same fate. Well, a girl’s gotta’ have fun while you’re away learning to fight to stay alive so you can return home for her wedding with Jody. Maybe your Cadillac was still there, slightly used. And probably your girl, too!

Courting with Jody invariably lead to the ‘Dear John’ letter received by untold numbers of soldiers once Jody got your girl. The letter of lost love, despair, and disappointment. Uncle Sam frequently delivered the bad news for the cost of first-class postage sent from halfway around the world. The all too familiar marching boogie was ain’t no use in looking down, ain’t no discharge on the ground held true. Keep your head up and on a swivel – you can find Jody and your discharge when you get home. Jody was every soldier’s enemy off the battlefield – and still is.

The guys you loved to hate and hated to love. Drill Sergeants – the guys teaching you how to stay alive in combat. The guys who marched your ass off doing the double-time shuffle with full field gear and your weapon held at port arms. Ugh, a killer!

Most Drills weren’t highly educated, but they had survived as infantrymen in combat. Survived firefights, ambushes, booby traps, hot & humid days, cold & miserable nights, cold C-rations, no beer.

Most wore the coveted CIB – the Combat Infantryman Badge – the badge of honor awarded to those so ordered to close with and destroy the enemy with direct fires. Some received the Purple Heart from their combat wounds as evidenced by visible scars or body deformity.

The fatigue uniform only allowed embroidered black subdued sewn on badges to be shown – the CIB, parachutist ‘wings, and the coveted Drill Sergeant Badge. The only glimpse of the colorful awards ribbons would be seen at the basic training graduation ceremony.

Drill Sergeants taught the spirit of the bayonet was to kill. If the bad guys got inside your personal space – using the bayonet could often be your last and only chance to survive. At the Battle of the Ia Drang in November 1965, the bad guys had surrounded the American 1st CAV unit commanded by LTC Hal Moore (later to become LTG Hal Moore).

As the bad guys were closing in for the final kill, the order was given to ‘fix bayonets and face to the front.’ The American infantrymen did fight in close-order hand-to-hand combat. Luckily some US soldiers survived and escaped for helicopter extraction several hours later. Garry Owen.

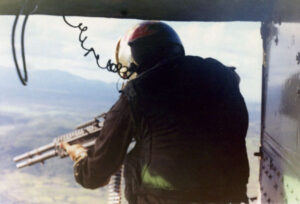

If ever a group deserved the ultimate valorous recognition, it was the door gunners on the Charlie model Huey gunship. To a man, each was deserving of the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for extraordinary valor and heroism. What other 18- or 19-year-old would stand outside a helicopter flying in a 120 mph windstream while firing a hand-held M-60 machine gun in the face of devastating return fire.

Without question these guys were the aerial infantry of the skies. Blazing away in front, to the side, underneath, and behind the fast-moving gun bird. Attached only by a six-foot nylon monkey strap secured to the helicopter, these guys would step out into open air, one hand firing, the other hand holding and feeding the belted 7.62 mm ammo into the gun.

Firebird door gunners were fearless in the face of danger. Most Charlie model gunship door gunners suspended their M-60s with a bungee cord while the ‘slicks’ door gunners had their M-60s affixed to a stationary pole mounted to the helicopter frame. Not the Firebirds gunners – stepping out into space, hanging on by a mere thread of nylon fabric, and blazing away in a modern day shoot out of aerial infantrymen.

Ground pounder grunts involved in a firefight were awarded the coveted CIB – the combat infantryman badge. The aerial acrobats were awarded the post-flight task of removing the spent ammo cartridges and links from the aircraft, being careful not to litter the ramp lest the Battalion Commander would be upset seeing the waste of war while on his semi-annual inspection visit.

The ground pounder grunts could hide behind trees or hug the ground. The sky shooters could hide only in thin air.

The reality of your (combat) service was, ‘most days were worse than others.’ There was only one ‘good’ day in Vietnam – that was the day you left country. All others, not good. The three days of a Vietnam service member’s calendar were today, tomorrow, and yesterday. Breaking 100 days to DEROS (date estimated return overseas) made you a double-digit midget, under ten days you were a single digit fidget.

The Freedom Bird was getting close.

The worst experiences and the worst duty were no doubt experienced by the grunts in the field. Slogging through the ‘bush’ constantly on alert for ambushes, booby traps, vermin, etc. Heat, humidity, monsoon rains, cold canned food, no shelter other than your poncho liner or maybe a foxhole. No Holiday Inn at night, no cocktail lounge or swimming pool. Just you and the enemy elements. Night patrol, night guard duty, no night sleep.

The best duty posts were Saigon, Danang, or the other larger population areas in the Central Highlands or along the coast. These areas featured Stateside-like duty, routine daily working schedules, access to civilized entertainment, food, billets, etc. Work areas were clean and well-kept using local laborers. Except for the infrequent enemy attacks, life was not bad in these areas.

The in-between places varied depending on location (coastal, flat land delta, highlands, etc.), living conditions (hooches, tents, bunkers), amenities (hot food, running water, laundry services) BUT it was still Vietnam. Nothing took the place of the USA!

Russ was the Hanley Hills neighborhood comedian. Russ and his wife Loretta were good Catholics – family of six kids, all living in a two-bedroom house in a post-World War II community. All the kids went to Catholic grade school and church on Sunday.

Russ enjoyed two things in life – laughing and drinking beer (maybe the beer made him laugh). No one knew for sure if he had a job, if he did, just what exactly was his job? He seemed to always be ‘in the neighborhood.’ He was kind to everyone.

A favorite time of year in our neighborhood was Christmas. Houses were decorated with multi-colored outdoor lights usually strung on the roof gutters. One neighbor had a lighted roof mounted display of Santa’s sleigh and reindeer being led by the red-nosed Rudolph. Russ was red-nosed year-round.

Christmas Eve and Santa – aka Russ – would make his rounds through the neighborhood. Kind of a reverse Christmas giving – Russ had no presents, but the neighbors fed Russ Christmas Eve Holiday Cheer.

Dressed as Santa and jovial if the beer flowed Russ would sit in your living room lighted by the massive Christmas tree and tell one joke after another. Russ was better than any late-night talk TV show comedian. Russ was THE late-night comedian.

The mid-1960s Christmas Eves were fun filled until Vietnam came along. After Russ’s second youngest son, Allen, joined the Marines in 1967 at age 18, he deployed to Vietnam in February 1968 and was killed in action on May 18, 1968. There were no more Christmas Eve visits from Santa Russ after that. Vietnam killed Allen physically and Russ spiritually.

No more jovial neighborhood outings, no more happiness in the Green’s household. Not all the casualties of the war died in Vietnam.

Dave and I raised our right hands together on July 24, 1967, at the Military Entry Processing Center, St. Louis, MO. We were US Army privates – grade E-1, enlisted to fight the evil NVA and VC in Vietnam as Army helicopter pilots. Swore our allegiance to the Constitution of the United States and to kill any and all enemies of America.

We soldiered together through basic training – kept a low profile never volunteering for anything and usually snuck out nightly low crawling along a drainage pipe to the PX beer garden. With a six pack of 3.2 Budweiser, Dave would call his wife Carolyn as I sat on a picnic table enjoying the evening but dreading tomorrow’s training.

After BCT, onward to Fort Wolters, TX to enter primary helicopter training. 20 weeks of initial training with flying and academics combined. Primary flight training finished, then Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah, GA for the final 16 weeks advanced training before Vietnam. Rode together flying to Vietnam with a smuggled fifth of Seagram’s 7 whiskey asking the stewardess for more water and ice! Landing at Cam Ranh Bay – we were ready to fight the war.

Dave went south to the 1st Cav Division while I was sent north to the AMERICAL Division. In October 1969, we returned stationed back at Hunter as instructor pilots. We enjoyed several years of beer drinking fun before going our separate ways.

Dave loved flying – he had a private pilot license before entering the Army. After leaving active duty he flew corporate helicopters in the Kentucky and Ohio areas. Unfortunately, he died on September 4, 1982, in a helicopter crash in Ohio. A great guy, friend, mentor, and one who looked out for me. Thanks for being such a great friend!

Barry Alexander graduated from Clemson University in South Carolina and died in Vietnam. All wartime deaths are tragic, but Barry’s death was sadly avoidable. He was ten days from leaving Vietnam after his duty tour flying helicopters in the 71st Assault Helicopter Company.

September 22, 1969, became known as Black Monday. Operation Frederic Hill was initiated with several companies of the 3rd Battalion/21st Infantry Regiment being airlifted into an area containing an NVA unit of unknown size. (Whatever possessed ‘higher ups’ to combat assault against units of ‘unknown size’ is a military mystery). The 71st AHC would provide combat assault support to the 3/21 as the 196th Brigade Commander rode safely above the fray and ensuing carnage.

The pre-briefing for Frederic Hill assigned mission aircrews.

Barry pleaded with his platoon leader to release him from this assignment. With ten days remaining in-country, Barry wanted to play it safe. There were reserve pilots available for the mission (most notably in Operations or the supply room) but Barry was told to fly.

Barry was killed instantly while crash landing the first lift of infantry into the landing zone. His wounded co-pilot was successfully evacuated from the downed helicopter and carried to a rescue aircraft. SP5 Thomas Brown carried the wounded 1LT Tom Gates under fire (they were all under fire) from the downed aircraft to an evacuation helicopter. SP5 Brown was awarded the Silver Star for his heroic action.

The 71st company commander in the lead aircraft immediately left the battlefield and retreated to the safety of the 3/21 Battalion Tactical Operations Center atop LZ Center to ‘coordinate’ the battle from there. The combat action was too hot for a REMF C.O.

The fight continued unabated for almost five hours – three 71st aircraft were shot down, 5 KIAs, 18 WIAs. Numerous heroic and valorous rescue actions by 71st crews in the ongoing battle.

Because these actions were witnessed firsthand by the company and brigade commanders, every crew-member received an award. As the Army then was often prejudicial with respect to ‘rank,’ the awards took on a hierarchical classification. All the pilots-in-command received the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), the co-pilots and enlisted crewmembers received only the Air Medal with ‘V’ (valor) for their actions.

The door gunners covering everyone’s ass may not have been ‘on the controls’, but neither were the pilots hanging out of the aircraft with M-60s blasting away at the attacking bad guys.

The Brigade Colonel Commander riding safely high above almost certainly received a DFC as well. Ask the 196th Brigade awards and decorations clerk who wrote up the awards recommendation. Rank always has privilege.

In truly prejudicial ranking the Army ignored the actions of the crews fighting their way in & out of the battle area. The higher your position, the higher your award. The Orderly Room Army doesn’t recognize that all crewmembers contribute in the battle engagements.

Barry Alexander was awarded an earlier than expected return to South Carolina in a Flag draped coffin. RIP Barry.

Army flight school graduates a pilot with 210 flight hours – barely enough ‘flight time’ to start the aircraft. Vietnam combat flying teaches a pilot how to fly in various configurations. Combat assaults, re-supplies, tight LZs, maximum weight loads, all give a pilot confidence and experience. But, to really learn and understand the true capability of the UH-1 Huey – become a maintenance test pilot.

With a few weeks remaining in the Firebirds, my duties shifted to helicopter maintenance activities. Instead of daily mission flying my function was working with the maintenance platoon keeping the Firebirds gunships mission ready. It’s where I met Ernie Isley – the man who taught me how to really fly the Huey. Ernie was probably THE BEST pilot in the unit and I was fortunate that he shared his skills and talents with me before my return to the USA. A fine man and a great pilot who died in 1995 following a heart attack. He was always wired!

The Rattlers and Firebirds experienced three POWs in 1968 and four MIAs in 1970. All three POWs were returned safely to the USA in March 1973. The four MIAs were not as fortunate – but all four remains were finally repatriated by August 2011. The two officers were buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery at Washington, D.C.

As of March 2021, 1,584 Americans including 28 civilians were unaccounted for in Southeast Asia. 442 still in North Vietnam, 802 in South Vietnam, 285 in Laos, 48 in Cambodia, and in China.

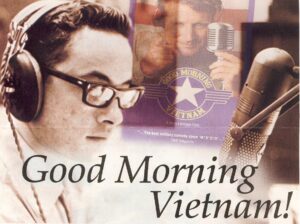

Before his death in 2018, Vietnam’s famous Gooood Morning, Vietnam radio’s DJ Adrian Cronauer worked with the Department of Defense Joint Recovery Agency. An attorney, he traveled to many countries where Americans remained unaccounted for.

(c) Copyright – 2023 – Vic Bandini