Every flight in Vietnam was unusual, almost all were fraught with uncertainty. There was never a way to determine the potential dangers that awaited. Preliminary information was given before the flights, but the situation would soon develop once the tactical elements were known. Several missions were more than unusual in my experience in the Summer of 1969.

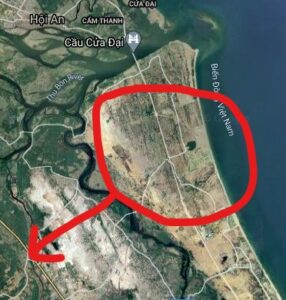

Mid-August was a devastating month for the Firebirds, especially after Kelly McHugh was wounded and medevaced to Danang (where the combat surgeons miraculously saved his leg). A call out was received from the 196th TOC advising a U.S. grunt unit was in contact with a large concentration of bad guys near the Hoi An Area. The American grunts had surrounded the NVA guys in a large sandy coastal plantation tree grove.

My fireteam launched into the hot summer afternoon for the ten-minute flight to the tactical zone. Arriving overhead the grunt commander advised me of the situation and cleared me to free fire into the area. Before departure from Baldy, I had the crews load Flechette rockets along with the usual HE (high explosive) loads. Flechette rockets contain 4,600 small aerodynamically shaped steel darts that when released in mid-flight travel at near supersonic speed to their target. A very effective weapon against ‘soft targets’, i.e., the human body.

The ground commander marked his location with a smoke grenade and gave me direction and distance to the target area. OK – he wanted me to bring it in to within 25 meters of his position! I advised too close – Danger Close – bring it in was his reply. OK – get your heads down.

We rolled in hot expending both HE and Flechettes. After several passes, and once the smoke had cleared, the grunts moved into the area for battle damage assessment. What they found was more horrific than imagined. The ground commander called me with the news that the bad guys were found ‘nailed to the trees’. Best mission ever!

The luxurious Vin Pearl resort now occupies this same formerly war-torn sandy grove that was a massive killing ground in August 1969.

In May 1968 the NVA caused the tactical evacuation of the small village of Kham Duc located on the border with Laos. Over 800 were evacuated using US Air Force C-130 transports operating from Chu Lai. Kham Duc had been surrounded and was under bombardment when the evacuations began. The Air Force crews were heroic – the aircraft were under fire when on the ground and tragically one crashed after takeoff, overloaded, unable to clear a mountain ridge after liftoff.

August 1969, I was assigned a reconnaissance mission to overfly and observe the Kham Duc airfield and surrounding areas. The region had been unoccupied since the devastating evacuation of May 1968. The one-way 60-mile flight took 30 minutes, 15 minutes for observation and surveillance, another 30 minutes return to Chu Lai. 75 minutes flight time with almost no fuel reserve.

Flying over the triple canopy jungle on the return flight, a bright silvery glint reflected from the treetops below. Catching my eye, I started a slow descending turn over the treetops advising my crew to let me know when it was sighted.

The silvery glint turned out to be the intact fuselage of a C-46 Dakota model transport aircraft laying in the upper jungle canopy treetops. Lower and slower we descended – one of the door gunners was able to read the faded and weathered black tail numbers on the aircraft’s tail. The entire aircraft was weathered, there were no attached wings, and all the fuselage windows had long since broken open to the weather elements.

The aircraft tail numbers were radioed to company operations. After landing, Operations advised that aircraft belonged to the French air force and had been listed as missing in 1954! 15 years laying above the jungles of Southeast Asia. What happened to the crew? Were skeletons inside the aircraft? There were signs of canvas straps hanging down from the mostly unbroken wreckage – did the crew rappel down to the jungle floor? Questions never to be answered.

Nighttime extractions of infantry units while under fire is one of the most stressful and harrowing of any missions flown by helicopter crews. The missions involve the helicopters performing the extraction of the grunts, the gunships protecting the extraction elements, an overhead ‘flareship’ dropping night illumination (safer than dodging the gun target line from artillery illumination rounds), and lastly, the high overhead C&C (chaos and confusion) helicopter with the ‘Combat Colonel’ riding the jump seat. (The combat colonel is logging time for adding an Air Medal to his ribbon rack).

The ground grunts are under fire, the slicks are inbound for the pick-up, the guns are orbiting on station to deliver suppressing fire protecting the extraction helicopters. The PZ (pick-up) is marked and identified as the flareship begins tossing illumination canisters over the area. Meanwhile the Combat Colonel flying high above is breaking into the radio net with nonsense chatter.

The extraction is underway, both the extracting helicopters and the gunships come under fire. The downward drifting flares provide nighttime/daylight for the operation. Red tracers are arcing through the air from all the helicopters. Tracers everywhere in the air, red hot tracers ricocheting off the ground, constant radio chatter between the helicopters. The real danger is the burning flares – burning out too close to the ground and they burn with no effect. Burning out too high, and the large silver unlit canisters create a huge inflight hazard if caught in the rotor system of an orbiting helicopter. Not good!

Move, shoot, and communicate – and hope you don’t snag a descending and dying flare. Many minutes of mayhem and madness – mission accomplished. Sign off the logbook entry for the Combat Colonel as proof for his Air Medal that will be upgraded to the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) by the ORA (orderly room Army – never defeated in battle).

(c) Copyright – 2023 Vic Bandini