Wars of enormous importance are fought in places nobody cares about – James Lee Burke – Feast Day of Fools

Holey moley! Orders for the First Cavalry Division was my assignment out of flight school in August 1968. The Cav as it was called. The Cav – Airmobile. The Cav – Cong killers. The Cav that fought in the Battle of Hue during Tet, 1968. Charlie Troop, 1st/9th Cav – had the highest aircrew casualty rate in Vietnam. The Welcome Wagon greeted you with a personalized body bag. Welcome to The Cav.

Holey moley! Orders for the First Cavalry Division was my assignment out of flight school in August 1968. The Cav as it was called. The Cav – Airmobile. The Cav – Cong killers. The Cav that fought in the Battle of Hue during Tet, 1968. Charlie Troop, 1st/9th Cav – had the highest aircrew casualty rate in Vietnam. The Welcome Wagon greeted you with a personalized body bag. Welcome to The Cav.

In 1967 a nineteen-year-old, single male without any qualifying deferment from the ‘draft’ discovered a universal military math formula. With an expired 2-S school deferment and a 1-A draft classification notice from the local draft board #236 the Army was not far behind. 2S/1A=11B – the non-algebraic translation is: losing your student deferment (2S) divided by your draft status (1A) means you’re next to go; and 11B means you’re gonna’ be a rifle infantryman in the jungles of Southeast Asia. But I had a plan.

I would endure my year-long tour as a combat helicopter pilot mostly unscathed. Along the way I would be shot down on fire, almost court martialed, survive a crash and splash into water filled rice paddies, fly into Laos as an unwitting mercenary without military or personal identity, hear the buzzing bullets, see the brightly colored tracers flashing around and through my aircraft, and defy the demons of death countless times. God truly was my co-pilot.

Dave Austin sat beside me in the Seaboard World Airways DC-8 charter jet as we winged our way westward to Vietnam in early October 1968. We had been side by side since joining Uncle Sam’s Army at St. Louis, MO in late July 1967. Raised our right hands together swearing our Oath to defend the Constitution and kill all its enemies. Same basic training unit, same flight school class. Same flight to Vietnam. Brothers Forever!

The Vietnam arrival at Cam Ranh Bay (CRB) was less dramatic than anticipated. Visions of running off the aircraft to the bunkers while under fire were simply untrue. So untrue that the arrival was more like stepping into a tropical resort and being greeted by khaki clad tour guides. Yes, they were tour guides, but not the type found in luxury resorts. CRB was a huge relaxed logistical base for the Army.

Everyone from clerks to colonels was redistributed through this in-country replacement unit – the CRB repo-depo. Each plane load of 200 plus new arrivals is housed in transient billets (think barracks) for a few days while the personnel administrators sorted out where to send you. A massive game of plugging in names to match current unit needs, ignoring previously issued orders.

Although my original orders assigned me to The Cav, the government changed them without notice or excuses. We hung around the billets watching the ‘permanent party’ personnel cook out and drink beer in the evenings. No alert status, no combat gear, just shorts, T-shirts, grilling steaks, and beer. I thought there was a war on.

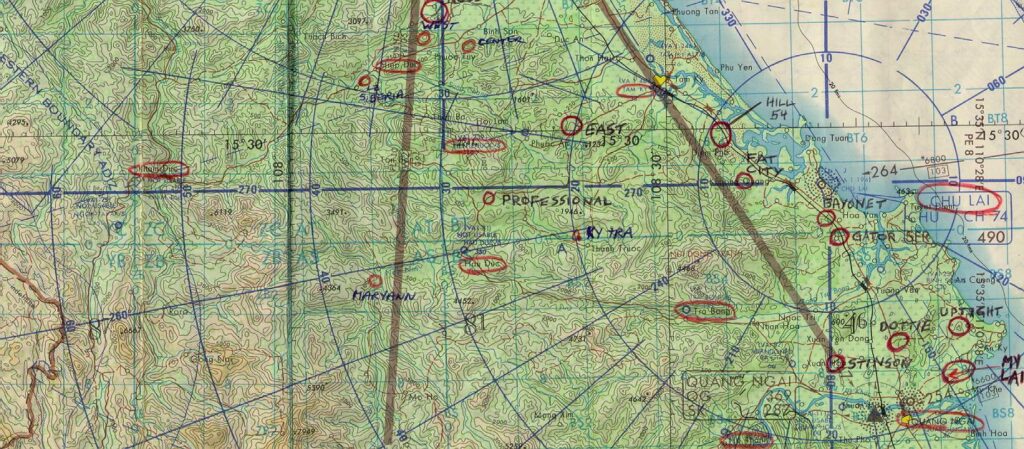

As expected, Dave went south to The Cav – while I was reassigned (for the convenience of the government) to the 14th Combat Aviation Battalion (CAB) 300 miles north near Danang. The 14th CAB was part of the infamous AMERICAL Division whose tradition began during World War II in New Caledonia under the Southern Cross constellation. Unfortunately the AMERICAL would be vilified following the My Lai massacre revelations of March 1968.

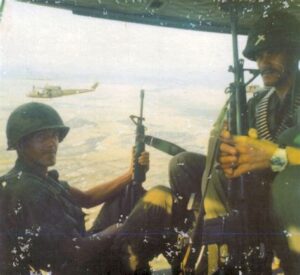

Flying aboard the Huey helicopter at 1,500 feet en-route to Danang provided stunning views of Vietnam that offered a panorama of the South China Sea, the villages, peasant hamlets, rice paddies, with the mountainous terrain as a backdrop. As I would soon learn, air temperatures are cooler high above rather than flying down low on the deck. But I always flew down low, just above the jungle tree tops, and barely above the rice paddies.

The tourist flying ended at Danang and the war began.

Wasting a few days in Danang allowed me to survey the unit personnel rosters of the 14th CAB units. A flight school classmate and close friend – Kelly McHugh – was in the 71st Assault Helicopter Company at Chu Lai, wherever that was. Took a chance, requested the 71st Rattlers and Firebirds, and the sarge in charge said OK and viola`, a day later I was hopping a Rattler slick heading 60 miles south to my newly assigned unit. Little did I know at the time while flying past LZ Baldy just west of Highway 1 that Baldy would become my operational base and intermittent home for most of my Vietnam tour in the Firebirds gun platoon.

Checking in at the 71st orderly room wearing bright green jungle fatigues identifies you as an FNG. F***ing New Guy – it’s just the way it is. Checking in greets you with the company clerks, the unit First Sergeant, and maybe the commanding officer. Between the platoon leaders, the clerks, and probably a clairvoyant – you are assigned to your platoon and sleeping area – mine was the F Troop, 2nd platoon.

All the hootches were constructed of plywood sides with open screens to catch the sea breezes, and galvanized tin roofs. Every hootch was elevated a few feet above the sandy soil of the South China Sea beach with multiple sandbags holding down the tin roof. Sandbags had various uses – keeping the roof on during the windy, rainy monsoon season and more importantly during mortar and rocket attacks. Of which there were always too many.

The ’company area’ of the 71st could have been idyllic. The entire unit was a beach setting situated on the South China Seacoast. All housing and other life support facilities in the company area included the orderly room (company headquarters), mess hall, showers and latrines, motor pool, supply room, plus three clubs – one each for officers, senior sergeants, and enlisted personnel. Company personnel were housed in over 40 hootches dispersed across the sand.

All the hootches and other accommodations had the same building codes and complied with all local zoning permits – namely, plywood sides and flooring, tin roofs, sandbags and community bunkers to shelter in the event of the frequent nightly mortar and rocket attacks. A combination entertainment stage and large movie screen was located on the beach.

But palm trees, chaise lounges, cabanas, Tiki bars, and scantily clad ladies were nowhere to be found. Sandals Resorts with the sandy beaches and South China sea breezes would be in the future of a liberated Vietnam. Who knew?

Most Vietnam flying experience begins in the lift platoons. In an assault helicopter company, there are two lift platoons (slicks) used for troop transport, field resupply, command & control observation, or other miscellaneous missions. The third platoon is the armed or gun platoon assigned to assist the lift platoons. Every assault helicopter company crew member begins his life in the lift platoon.

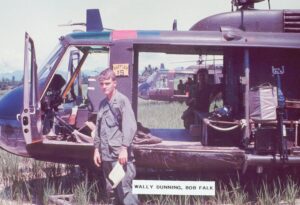

Rule number one in the slick platoons is the crew chief oversees his helicopter. It’s his aircraft and his responsibility to maintain it in flyable condition. A good buddy is his door gunner, and both are charged with keeping the aircraft in top condition. Most of their non-flying time was spent at the flight line appropriately named the Snake Pit. The helicopters were parked side by side in protected separate revetments.

A large open-air hangar accommodated helicopters undergoing periodic or other maintenance and repair activities. The maintenance hangar functioned around the clock. Airframe repairs, sheet metal fabrication, turbine engine cleaning was a continuous non-stop event. A large separate platoon was devoted to this operation. The simpler dailies (daily maintenance) and pre & post flight inspections were the routine repertoire.

The door gunner, along with the unit armorer, ensured the M-60 machine guns and relevant spare gun parts and lubricants were always on hand. A thankless job but one undertaken with pride and respect. Sometimes pilots were allowed menial tasks such as cleaning, shining, or washing any non-mechanical helicopter functions and only with permission from the crew chief. Officers needed to ask.

Early morning departures from the Snake Pit flight line was the norm. A few cases of C-rations were always aboard for casual eating during the day. No scheduled stops near mess halls, try to eat an early breakfast in the company mess hall and maybe you’ll get back in time for the evening meal. If not, there is an overnight hot ‘mid-rats’ meal in the company mess hall. Eat when you can and sleep where you can.

Nothing beats a can of cold congealed spaghetti and meatballs in the morning atop a fire support base. Of all the various meal packages in a case of C rations, peaches and pound cake was most coveted. Ham and lima beans most despised. Sleeping was allowed inside, underneath, or atop the helicopter. Depending on the weather.

The aircraft commander briefs his crew for the coming day’s flight activities. Supported units, locations, mission types all explained prior to lift-off. Maps of the AO and the SOIs (signal operating instructions) are held by the aircraft commander (a/c). The A/Cs used their own maps with most of the prominent and important American bases distinctively marked. SOIs were small, multi-page paper booklets listing the unit coded call signs with assigned radio frequencies. It was a big no-no to lose an SOI for fear that some VC ham radio operator could listen in.

Another important item was your ‘chicken plate’ – upper body armor worn in a heavy canvas over the shoulder harness. Pilots wore theirs – the crew chief and door gunners sat on theirs. With an empty aircraft, the early morning 30-minute flights to the 196th units were usually uneventful. Usually, sometimes, uneventful, sometimes.

Once on the ground at the LZ resupply pad, the grunts took over assembling the first round of resupply packages for the field units. The crew chief supervised the loading while the door gunner assisted. Load distribution and estimated weights were monitored by the crew. With time and experience, the slick crews became excellent loadmasters.

If it’ll hover, it’ll fly – most times. Resupply delivery depended on current unit field locations. The field commander or platoon leader would radio transmit their current field location along with their supplies request to the battalion operations center (BTOC).

Because the smaller units frequently changed field locations, this information ensured an accurate delivery address. The BTOC relayed the request to the supply guys who organized the supplies and moved them to the resupply helicopter. Current map coordinates, unit designation, radio frequencies or updated information were provided to the slick a/c.

Resupply missions involved long days, early morning departures from the Chu Lai base camp and almost always late arrivals home after dark. When not flying resupply missions, aircraft could be redirected for other uses during the day. Lots of down time and waiting was sometimes the norm.

Several pilots would log 1,200 to 1,400 flight hours in their yearlong tour of duty. Pilots were restricted to a maximum of 140 flight hours in a 30-day period without obtaining medical clearance from the battalion flight surgeon. Crew chiefs and door gunners could fly their asses off.

Completing the daily missions for both the resupply birds and the C&C birds meant a brief stopover at LZ Baldy for more fuel and a visit to the small airfield to say hello to the Firebirds parked there. The other reason was transporting hitchhikers to AMERICAL headquarters at Chu Lai. Often the pax could be delivered to the Division landing area, but if not, flown to the Rattler Snake Pit base from where they could catch a ride on the road to wherever.

The fun part of the nightly ‘back haul’ was seating high ranking NCOs near the open doorways. Remembering the awful days of basic training treatment, the warrant officer pilots had their chance for payback. Most slick helicopters were equipped with an encrypted radio known as the KY-28. Operating on the FM radio band the KY-28 would allow scrambled voice transmissions with selected or other matching KY-28s on the same frequency.

The KY-28 was a piece of airborne junk and never used – however, when an aircraft went down the KY-28 had to be evacuated less the VC radio ham operators intercept the chatter. An absolute waste.

A small green light was located on the helicopter’s interior cabin ceiling that would illuminate when the KY-28 was operating. One favorite trick on the ‘choppers to Chu Lai’ after dark flights was to bump the KY-28 ‘on’ switch – the green overhead light would be flashing intermittently driving the unknowing grunts crazy!

The senior NCOs were usually older than the regular grunts and sometimes apprehensive about flying. Good! The 30-minute flight to Chu Lai allowed time for sky-high antics with tight corkscrewing turns down to low level flight either along Highway 1 or the beach (feet dry or feet wet). Racing in the 110 miles an hour open-air breeze it was humorous watching the white knuckled senior sergeants grabbing their seat frames trying not to puke into the open sky.

This was payback for miserable treatment and harassment that most flight school candidates endured from their basic training Drill Sergeant peers. But sometimes forgetting these very experienced veterans were teaching us the art of staying alive in combat.

There were no in-flight refreshments, nor did anyone leave large tips upon arrival. They all disembarked and hurriedly trudged away – some may have been lucky and on their way Home.

(c) Copyright – 2022 – Vic Bandini