In the war of insurgency, it’s difficult to distinguish the good guys from the bad. But what about distinguishing between the ‘good guys?’ How does one distinguish the ‘good’ good guys against the ‘not so good guys’ without finding trouble? That happened to me one night in August 1969.

Night FireFly missions are dangerous and difficult missions for many reasons. One, if you are the FireFly, you’re flying low, slow, and below a safe altitude. Low and slow to allow the FireFly light to penetrate the dark night. Low and slow to look for the bad guys moving surreptitiously away from discovery. Below a safe altitude that provides a comfort zone from enemy ground fire. Below a safe altitude that permits a successful recovery from an unforeseen aircraft malfunction.

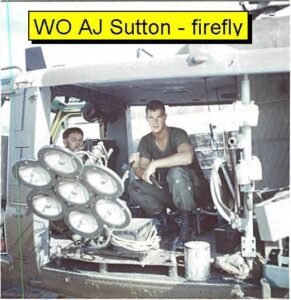

The FireFly is a large light system made up of several helicopter landing lights modified into a large frame mounted in the side door opening of a UH-1 Huey helicopter. The FireFly light can make the Sun shine on the darkest night.

The FireFly team needs four helicopters – one carrying the light, one flying command & control (C&C) high above the planned flight route, and usually two gunships between the FireFly and the C&C bird.

The ‘high’ gunship provides cover for the FireFly helicopter and the low gunship. The low gunship flies ‘blacked out’ – no external marking or position lights shining. The ‘blacked out’ low gunship lurks and snoops for firing opportunities if the FireFly light illuminates a target of opportunity. Flying without position lights or external illumination gives no visible target and provides an element of surprise against ‘bad guy’ ground gunners. In mid-August 1969 I was the Fire Team Leader (FTL) and in command of the low gunship on just such a FireFly mission.

The assigned mission was received through Rattler operations command channels. Aircraft and crews were assigned outside the usual Firebird rotation schedule, I drew the mission. The mission briefing took place about 10:30 PM in the Rattler mess hall where the aircraft commanders, operations staff officers, and Vietnamese Army (ARVN) interpreter met to discuss the coming night’s mission.

One US Army liaison officer accompanied the mission with the interpreter. Pre-brief explained we were to fly and follow a stretch of river several kilometers south of our Chu Lai base camp. The map reconnaissance laid out the flight route, radio frequencies were exchanged, and the rules of engagement confirmed. The rules of engagement that night allowed a ‘free fire zone’ all along the designated flight route – no friendly troops were reportedly in the area. No sweat this will be a piece of cake! If it moves, shoot it!

Launch and flight into the Song Tra Bong river area south of Chu Lai went without incident. All aircraft were operating normally, radio contact was established, and the in-flight briefing confirmed the earlier pre-brief at the Rattler mess hall. The Vietnamese Army (ARVN) interpreter and the US Army liaison officer assigned to the mission were aboard the C&C helicopter.

Both Rattler company operations and the ARVN command network (through the interpreter) gave me clearances to begin the mission. The aircraft assumed a stacked flight formation for the FireFly mission profile; C&C helicopter above; then the high gunship, and me in the blacked out low gunship following the even lower FireFly ship. In the darkness we descended toward the river and a soon to be unpleasant fate.

The summer midnight was cloudless and moonless, clear and dark with no winds to buffet us. The terrain below was a mixture interspersed with green blotched rice paddies and tan colored sandy areas along the river’s edge. The soft red glow of aircraft instrument panel lights dimly lit the interior of my gunship. The Firefly light ship slipped into its low altitude flight path with my invisible aircraft trailing a short distance behind.

Intercommunications inside my gunship were ‘on’ and my co-pilot, WO Rusty Glenn, retracted the 40mm cannon-sighting device from the left overhead. Rusty peered into the target reticle sight as both door gunners maintained ready alertness. We flew along in silence for a few minutes following the Firefly keeping distance while maintaining radio silence. Then the Firefly suddenly illuminated it’s bright sunray light toward the ground.

As we approached a slight bend in the river a bright white tracer-like projectile shot upward from the ground toward the light ship.

Without hesitation Rusty began firing the 40-mm cannon. The Firefly pilot called over the radio that he was receiving ground fire from his three o’clock position. Rusty continued firing away, chunking and ‘walking’ the 40-mm grenade projectiles through the area where the ground fire had originated. The exploding ground impact 40-mm rounds reminded me of silver popping camera flashbulbs.

Radio chatter began between the C&C, Firefly, and me. Confirmations of firing locations, type of weapons, all-talk above the rattle, thump, and din of our return fire. After a few brief seconds the single round ‘ground fire’ burst into an illumination ‘star’ flare. I recognized that the starburst flare was not enemy fire as it illuminated a small encampment of tents near the riverbank. Immediately I shouted a ‘cease fire’ through the gunship intercom. It was difficult hearing the command above all the noise and racket of gunfire. Several more commands were given before the shooting finally stopped.

As the Firefly ship passed over the encampment, we knew that we had inadvertently fired into an area of troops. At least the shooting had stopped. I called the C&C aircraft and asked for the ARVN interpreter or US liaison and more explicitly wanted to know what in the hell was going on. ‘No friendlies’ in the area was in the mission pre-brief and a ‘free fire’ zone was in effect – ‘return fire’ if/when fired upon. We did return fire! After several confusing moments it was decided to cancel the mission and return to Chu Lai.

A post mission report was filed at Rattler operations but not before some heated exchanges between me and the US Army liaison officer who accompanied our midnight mission. If you have ever been in a combat situation gone bad, you can imagine the language and gestures involved. We returned to the company area for rest and sleep.

A few days later as I am enjoying a day ‘off’ in the Firebird party room, a company clerk advises me to immediately report to the Americal Division headquarters. The clerk implies it has something to do with the Firefly mission a few evenings ago. My first thought is great, but why do I have to go to Division HQ to discuss that screwed up mission?’

The shock of my then-life greets me as an Army major dressed in a tan Class ‘B’ rear echelon uniform sitting in his air-conditioned office informs me that I am under Article32 investigation of the UCMJ (Uniform Code of Military Justice). Article 32 is the investigation authority pursuant to military courts martial. ‘Why?’ I ask. For the ‘alleged’ killing of three Army of Vietnam (ARVN) soldiers because of firing from the aborted Firefly mission is his response. News to me! And doubtful of any ‘justice’ here!

As this is a preliminary investigation, I was advised that counsel was not necessary. The major would function as the appointed judge, jury, and maybe the executioner. ‘So, what’ I figure – I did nothing wrong. The mission was properly briefed (albeit with bad information), a US Army liaison officer provided the proper clearances, and the ARVN interpreter was in radio contact with his headquarters command network.

Only the major did not see the situation exactly as I did. Were you Mr. Bandini in command of the flight and the gunships! Yes, I was. Were you responsible for the shooting – yes, I was. YOU then are responsible for the three dead ARVN soldiers! Wow! How did this happen to me? It was a ‘free fire’ zone.

Dismissed with instructions to prepare my statement, I gathered my thoughts as best I could remember of the failed Firefly mission. During the following days, the investigating officer continued his interviews and questions in preparation for courts-martial proceedings against me. Finally, I asked ‘What evidence is against me?’ ‘Where is the US Army Captain who was the liaison officer that night and gave mission and ‘free fire’ clearance?’ and ‘Where is the ARVN interpreter who gave information that no friendlies were in the planned mission area?’ And most importantly where are the dead guys? The major only shrugged and said that both individuals were unable to be located. Something is not right.

When you celebrate your 21st birthday in Vietnam and have escaped death as a helicopter gunship pilot for almost a year not much really worries you other than catching the Freedom Bird back to the ‘world.’ So, although troubled, I wasn’t too concerned with my fate at that point. A few more days passed before word came from the major at AMERICAL Division. When I reported back, he informed me that no other witnesses could corroborate the ‘alleged’ three killings.

The ARVN interpreter had suddenly vanished into a rice paddy somewhere and the US Army Captain had mysteriously and handily transferred to the Saigon area. The three ARVN soldier’s bodies could not be found. And, because of these circumstances all charges against me were immediately dropped. I was free to leave and continue killing.

Returning to the Firebird party room that afternoon was a welcome relief. As a reminder to the other guys, I nailed my five-page legal pad statement onto the wall behind the Firebird’s party room bar. Less than 60 days to go and I’ll be back Home. No more weenie crap, no more rear echelon desk drivers second guessing you about flying and fighting in an unwinnable and senseless situation that required a clearance from the REMFs in rear area TOCs before you can return fire. No more trying to figure out who and where the bad guys really are. Then I remembered what my Dad once told me, ‘Dead men tell no tales.’

(c) Copyright – 2023 Vic Bandini